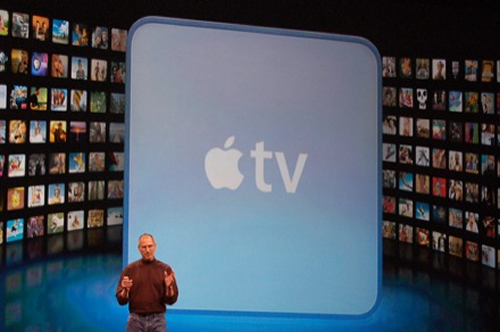

Steve Jobs Stakes Out the TV Den

I don’t own my iPod. It owns me.

A week ago, the family was stuck on I-95 between Washington and New York for seven hours. The Meatgrinder, as it is affectionately known to us, had a little case of congestion and after five hours of quality time, we were reduced to silently hating the intermittent FM signal and the brake lights that framed our existence.

But after we hooked an Apple iPod to a doohickey that works with the radio, the car suddenly filled with an hour’s worth of storytelling from a podcast of “This American Life,” followed by some quality time with Taylor Swift, an improbably gifted teenage country star. The ability to program our temporary purgatory lifted the pall and before we knew it, we were home.

But once we went inside, we hit the halt button on Apple. There was the second season of “Friday Night Lights” on Netflix, “John Adams” from HBO on the digital video recorder and back copies of “Weeds” from Showtime, there for the plucking from the on-demand service.

While a lot of us carry a little bit of Steve Jobs around in our pocket, Apple is now after the remaining bit of life-share that it doesn’t already own, the home front.

On Thursday, the company announced deals with 20th Century Fox, Walt Disney Studios, Warner Brothers, Paramount Pictures, Universal Studios Home Entertainment and Sony Pictures Entertainment, among others, to sell movies for download on iTunes on the same day they are released on DVD.

The “day and date” downloaded movies (as they are called in industry jargon) will play only on Apple gadgets, but that characteristic may finally give the company the toehold in the American den that it has been looking for via Apple TV.

The movie business, because it makes its living on big fat video files that are harder to share than audio files, was able to watch and learn as the music industry shrank under the weight of pirated downloads and then reluctantly embraced a 99-cent solution from Mr. Jobs. And now every song, now and forever, is worth 99 cents, a price that attains for both the red-hot duet by Madonna and Justin Timberlake “Four Minutes,” and the forgotten B-sides he made when he was in a boy band.

The music companies still owned the songs, but Apple owned everything else — pricing, format, distribution and the lucrative revenue stream of manufactured devices.

When it comes to video, Apple has competition. Microsoft, Sony and Hewlett-Packard are vying to offer Web-enabled TV, while Amazon, Blockbuster, CinemaNow and Netflix sell movies digitally. So unlike the music companies, the movie studios seemed to be holding most of the cards.

They still might have blown it.

On the surface, it looks like a great deal for the studios. Apple has agreed to sell new releases for $14.99 and rent them for $3.99 while older, “library” movies go for $9.99 and cost $2.99 to rent. It’s a reasonable price to pay the studios for electronic sell-through, especially when you consider Apple is paying more for the releases than it is charging consumers ($16, according to The Wall Street Journal). That follows Wal-Mart’s use of entertainment as a loss leader to get shoppers in the door.

Given that online movies sales are a tiny business — under $100 million — and that Apple has sold only seven million movies compared with four billion songs, it would seem like a blip. But Mr. Jobs is in the business of changing every game he plays. In spite of the fact that Apple TV — which feeds video from the Web into your television — initially tanked, this latest grab may help Apple take a huge bite out of the home entertainment environment.

Studios may own the copyright and content, but if Apple achieves anywhere near the penetration in movies that it has achieved in music, the studios could become vassals in a closed digital community, ginning up content that is controlled, priced and distributed by someone else.

The movie industry has always wanted to maintain custody of the user experience — in the theater, on home video and on television, which is why you once had to wait for Easter every year to watch “Ben Hur” on the Magnavox. But content’s claim on the crown is being challenged by the user interface that controls the experience. And nobody makes that experience easier than Apple, which came out with a 2.0 version of Apple TV in February that is a beaut, with an intuitive, practical interface and a $229 price that may have consumers taking a second look.

Recently, I downloaded “Dan in Real Life” for $14.99 on iTunes. It took 42 minutes and took up one gigabyte of precious storage space. My new movie will play on my computer and iPod, but not my television without a lot of jerry-rigging. If I had Apple TV, it would have taken up space there, begun playing almost instantaneously and been viewable on the gorgeous widescreen television in my den. (It’s actually a generic 19-inch set I bought at Costco, but you get the idea.)

That makes another Apple device sound pretty handy. But if I buy my movies from iTunes, I will be handing over custody of my film library to Mr. Jobs. (I love my iPod and all 3,000 songs I have on it, but if I had it to do over again, and now I do, I wouldn’t have entered a lifetime partnership with Apple.)

The studios may end up with a similar feeling, having helped Apple build another hardware franchise on the backs of their content. Executives from four studios I talked to said Apple’s purchase on American consumers means the folks from Cupertino will be a player no matter what and pointed out that just sitting still didn’t work out so well for the music industry, with consumers eventually just stealing what they could not buy.

Kevin Tsujihara, president of the Warner Home Entertainment Group, cautioned that the Apple deal is just one more game piece, not a game changer. Time Warner has the largest library and huge influence with it. He suggested that the deal with Apple is far less important than Time Warner’s own day-and-date video-on-demand service, announced by Jeffrey L. Bewkes, the chief executive, Wednesday.

“Apple is just one piece of the puzzle as it relates to digital distribution,” Mr. Tsujihara said. “They sell hardware and we sell software, and we had to come up with a pricing model that works for both parties and allows the consumer to legitimately access our content. The ultimate solution is coming up with a format that allows it to be played anywhere — in your car, on your PlayStation, on your computer.”

The lack of an open standard and the need for branded hardware is critical to Apple because it provides a revenue engine. If selling video online was a no-brainer, why have Amazon, Google, AOL and Wal-Mart, American marketing royalty, struggled to find a way to bring that future forward? If Apple wins, it will be driven by hardware, and regardless of what the studios do, their blockbusters and dramas will be commoditized.

It will take some time. Many homes are still not ready to share digital files; download speeds are sporadic; and the DVD remains the format of choice.

But going forward, everything is up for grabs. And when it comes to a jump ball, best to put your money on Apple.