Religion looms large over 2008 race

By TOM RAUM, Associated Press Writer1 hour, 46 minutes ago

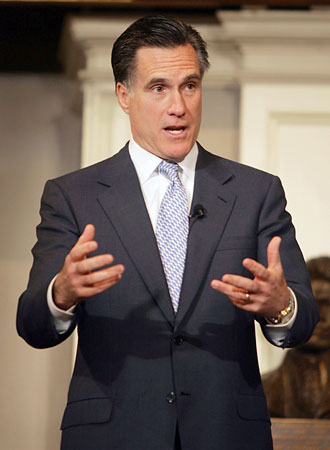

When George Romney ran for the 1968 Republican presidential nomination, his Mormon heritage was mostly a footnote. It was scarcely mentioned in news accounts of the day. But for son Mitt Romney, the family religion presents a formidable political hurdle.

The younger Romney repeatedly is called on to defend his membership in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its teachings, encountering skepticism particularly from Christian conservatives, a key component of the GOP base.

"I believe that there are some pundits out there that are hoping I'll distance myself from my church so that'll help me politically. And that's not going to happen," Romney asserts.

Religion has not played so prominent a role in a U.S. national election since 1960, when John F. Kennedy became the first Catholic to be elected president.

And it's not only Romney under scrutiny. All the Democratic and Republican presidential hopefuls have been grilled on their religious beliefs. Most seem eager to talk publicly about their faith as they actively court religious voters.

Democratic Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton emphasizes her Methodist upbringing and says her faith helped her repair her marriage.

Chief rival Sen. Barack Obama frequently uses the language of religion and proclaims a "personal relationship" with Jesus Christ. The Illinois Democrat — whose middle name is "Hussein" — scoffs at suggestions of Muslim leanings because he spent part of his childhood in Indonesia. He is a member of the United Church of Christ.

In the most recent Democratic debate, a pastor in a YouTube video asked Democrat John Edwards to defend his use of religion to deny gay marriage. The former North Carolina senator — a Methodist — talked about his faith and his "enormous conflict" over the issue

Republican Sen. John McCain, an Episcopalian, says, "I do believe that we are unique and that God loves us." Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee, an ordained Baptist minister, emphasizes his belief that "God created the heavens and the earth. To me, it's pretty simple."

Unlike the others, former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, a divorced Roman Catholic who favors abortion rights, sidesteps such questions, claiming one's relationship with God is a private matter. But he attended Catholic schools and at one point considered being a priest.

Clearly, the religious issue is the most problematic for Romney. Polls suggest he faces continued misgivings over his faith. An ABC News-Washington Post poll conducted July 18-21 showed that 32 percent of those who said they leaned Republican described themselves as "uncomfortable" with the idea of a Mormon president.

An earlier poll by the Pew Research Center said 30 percent of respondents said they would be less likely to vote for a candidate that was Mormon. The negative sentiment rose to 46 percent for Muslim candidates and to 63 percent for a candidate who "doesn't believe in God."

Pollster Andrew Kohut, Pew's director, said that between the late 1960s, when Romney's father ran, and now there has been "one of the great transformations of our era. There is more mixing of religion and politics than there was then. As a consequence, people scrutinize Mormonism — or any other religion — more closely than back then."

He cites the growing influence of the Christian right, the political activism of tele-evangelists and a trend that has seen a steady migration of Christian conservatives into the GOP fold, particularly in the South.

"When the South changed, it brought the evangelicals with it," Kohut said.

The links between religion and governance intensified with the presidency of George W. Bush, said Joan Konner, former dean of the Columbia Journalism School. "He brought it up when he ran for office and he said his favorite philosopher, in answer to a question in a debate, was Jesus.

"And then he followed up on that by faith-based public funding and various other actions that started to erode what Americans took for granted as the separation between church and state," said Konner, who has studied the interaction between religion and politics and is the author of "The Atheist's Bible."

George W. Romney was a politically moderate former governor of Michigan and auto-industry executive when he sought the 1968 GOP presidential nomination. Scant mention was made of his Mormonism in news accounts at the time and it appeared to be a non-issue in the race.

Polls showed him as the front-runner until he stumbled by complaining to an interviewer that when he had visited Vietnam, he had been "brainwashed" by military briefers there into supporting the war. That remark generated enough controversy to cost him the nomination.

Some historians suggest more attention might have been paid to Romney's Mormonism if he hadn't torpedoed his own candidacy so early. And in those days, many Christian conservatives were southern Democrats and less interested in GOP primary contests.

Romney withdrew as a presidential candidate on Feb. 28, 1968, just ahead of the March 12 New Hampshire primary won decisively by Republican Richard Nixon.

Mitt Romney supporters point to Kennedy, who overcame questions about his religion to become the first Catholic elected president. He did that, in part, by speaking before Protestant clergymen in Houston in 1960 to dispel fears that, as a Catholic president, he would be subject to direction from the pope.

Can Romney neutralize the religion issue the same way Kennedy did — by giving a major speech explaining the role his Mormon faith plays in his political life?

In an interview in Iowa with The Associated Press, Romney said he's considering dealing with the issue in a comprehensive manner, although "it's probably too early for something like that."

"At some point it's more likely than not, but we'll see how things develop," Romney said.

Kennedy had one advantage that Romney doesn't. When he ran, Catholics made up roughly 28 percent of the U.S. population. Although one of the fastest growing faiths in the world, Mormons represent less than 2 percent of the U.S. population with 5.5 million members across the country.

"The differences between Kennedy and Romney are in the nose count," said political historian Stephen Hess. "The religion issue may have hurt Kennedy, but it sure helped him at the same time" as Catholics threw their support behind him.

"There is no way that capturing the Mormon vote is going to win Romney anything," Hess said.