Warner’s Digital Watchdog Widens War on Pirates

LOS ANGELES, April 1 — Hollywood studios spend millions every year trying to get people to watch their movies. At Warner Brothers Entertainment, Darcy Antonellis is trying to get them to stop watching — illegally, that is.

Ms. Antonellis oversees the studio’s growing worldwide antipiracy efforts as Hollywood’s attention shifts from bootleg DVDs made in China to the problem of copyrighted television and movie clips showing up on sites like YouTube and MySpace.

While producers and celebrities garner most of the attention in Hollywood, technology executives like Ms. Antonellis are at the forefront of the industry as they try to protect the studio’s control over its content.

With movies like the “Harry Potter” series and “Ocean’s 11” franchise and television series like “Friends,” Warner has one of the largest libraries in Hollywood. As a result, it can exert more influence over its relationships with online partners, making it one of the most-watched studios both inside and outside the industry.

“People want to be more interactive and have a voice,” said Ms. Antonellis. “We need to consider all the opportunities.”

Piracy may seem like the biggest threat to Hollywood, but Ms. Antonellis suggested instead that changing consumer behavior will have a greater impact on the entertainment business.

Movie studios, like their peers in music and television, are in the midst of a significant and frightening shift as almost every form of media is becoming ubiquitous on the Internet. And through sites like YouTube, viewers have grown accustomed to seeing whatever they want to see, free.

“People thinking it is O.K. to take this stuff for free on a worldwide basis has a bigger impact than anything,” said Ms. Antonellis.

Many entertainment companies are growing impatient watching companies like YouTube distribute clips of movies and television shows free. At the same time they are concerned that YouTube earns advertising revenue from Web sites that offer pirated movies for sale on the site. Even while negotiating with YouTube, NBC Universal and Fox announced their own joint video service, and Viacom filed a $1 billion lawsuit against Google, which owns YouTube.

Missteps made today could have grave consequences for the future, particularly when it comes to consumers’ willingness to pay for movies and television shows online, she believes. To illustrate the point, she tells of her niece’s fish, named Mortimer, who one day leaped from his bowl, flopped on the table and gasped for air.

“Mortimer took the leap to freedom,” she said. “He said, ‘I’m free, but I’m dead,’ ” said Ms. Antonellis.

Warner and other entertainment companies are moving cautiously ahead, but their interests are divided. All want to share their content online with consumers but are, at the same time, imposing constraints that risk alienating a younger, Web-oriented audience.

On the piracy front, Ms. Antonellis said Warner has created four small teams that range from a two-person operation to nearly a dozen people in a larger group.

The teams are based in Burbank, London and Hong Kong, and most have dual roles in piracy and other Warner operations, like the legal department. Ms. Antonellis said she wanted the teams to understand both areas because “you can’t hand down policies in a vacuum. It doesn’t work.”

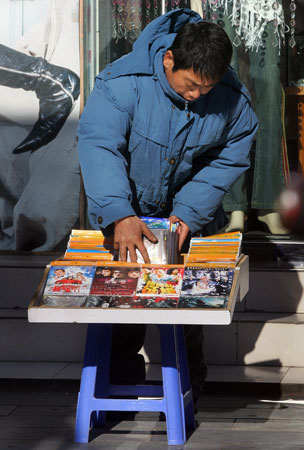

Warner’s emphasis shifts depending on where piracy is most rampant. As well as cracking down in countries like China, where pirated DVDs are sold on street corners for as little as $1 on the same day a movie is released, the company also works with the United States Trade Representative’s office to monitor pirated movies.

Like many studios, Warner can trace the origin of movies that have been copied using camcorders, but they are particularly aggressive on this front. Russia is particularly difficult to police because of the vast amount of money available to finance the making and sale of black market DVDs.

Recently the Hollywood studios took their case to Washington, with celebrities like Will Smith and Clint Eastwood in tow, to educate legislators on the damaging impact of piracy on their business. Ms. Antonellis was there; she is the piracy liaison for Warner to the Motion Picture Association of America, the industry’s lobbying group.

For her part, Ms. Antonellis and her team review all the deals Warner seeks, particularly those online and for distributing content over mobile phones. She has considerable sway; Warner deal makers rely on her expertise to tell them how a deal should be structured.

When it comes to YouTube, Time Warner is in a delicate position. In 2005, Google spent $1 billion for a stake in America Online, a division of Time Warner, and expanded its strategic alliance. Google bought YouTube last year.

Not surprisingly, Ms. Antonellis is conservative in her comments about the media companies’ negotiations with YouTube.

“Clearly the lawsuit has sent out a message,” she said of Viacom’s suit. “We are hopeful that social networks such as YouTube will put in place proper systems which will reflect our intellectual property and will facilitate legal offerings.”

Ms. Antonellis is the rare Hollywood executive who never planned on a studio career. The 44-year-old former college tennis pro hoped to become a journalist until, as she put it, she learned writing was not her gift. She had an aptitude for math, though. After her freshman year at Temple University, two hours from her hometown, Newark, Ms. Antonellis decided to sign up for the electrical engineering program instead.

She did not abandon her interest in news, though. She graduated in 1984 and headed to New York City where she got an engineering internship at CBS working with Chris Cookson, the chief technology officer of Warner Brothers Entertainment who was then an executive in the technical operations department of CBS. In 1988 she moved to Washington where Mr. Cookson appointed her director of Washington operations for the CBS news bureau.

“We’re the folks behind the curtain who make the broadcast look as seamless as possible,” said Ms. Antonellis.

If anything prepared Ms. Antonellis for a career in Hollywood, perhaps it was the two months she spent in Kuwait during the gulf war as director of technical operations for CBS News. Then she worked for well-known and demanding bosses, among them the news anchor Dan Rather. She was a skillful negotiator, bartering with locals for a generator to light the set. And she was quick to adapt, dressing like a military officer because women were not allowed to drive.

In Washington she was exposed to other divisions: sports, news magazines, even soap operas, which were sometimes filmed in the studio.

“One day the elevator door opened and a pot-bellied pig walked out,” said Ms. Antonellis, who has won two Emmy Awards for her technical prowess. “I thought, ‘O.K., we are doing a story on a pot-bellied pig. Do we bring him to the green room? Do we have to worry about him eating all the crudités?’ ”

She left Washington in 1991 and moved back to New York and worked in operations and engineering for CBS Sports, covering three Olympics, including the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano, Japan. That same year Mr. Cookson recruited her to Warner to help with the studio’s transition to a digital world.

“We share here a belief and understanding in new technology and that consumers want to experience our movies and television shows differently,” Mr. Cookson said. “Darcy really understands the whole equation.”

Ms. Antonellis believes that the next three months will be most critical for Hollywood as the need to offer legal movies and television shows to consumers intensifies. When asked about criticism that studios aren’t moving quickly to offer content online, she pointed to a deal Warner made last year with BitTorrent, a movie-swapping site that approached the Motion Picture Association of America about selling movies legally.

“We were criticized for not being aggressive enough,” she said. “At the same time, we can’t be faulted for being radical in our approach.”

Indeed, Warner spends millions in research to understand what consumers want. And the results can be surprising. In Britain, Warner recently found that consumers there were more interested in watching feature films, as opposed to television programs, on portable devices because their commutes were twice as long.

“If we don’t encompass the last piece in our thinking — how consumers want to use content — then we are going to miss it,” said Miss Antonellis. “Just think how consumer behavior has evolved in the last two years.”

Last year Steven P. Jobs, the chief executive of Apple and a director of the Walt Disney Company, announced a deal with Disney to offer movies on Apple’s video iPod. Despite that, many of Disney’s competitors remained holdouts. At the heart of the debate are the standards governing digital rights management, commonly called D.R.M. Studios want stricter rules on copying, while Mr. Jobs supports a more liberal approach, particularly with music.

“There may be opportunities down the road but we have to come to some agreement about what the offerings will be,” said Ms. Antonellis of Warner’s and Apple’s discussion. “The term D.R.M. is steeped and mired in its legacy definition. Today, call it something else. I don’t care what you call it. Get rid of it. But we need to make this work so we can get a deal.”

Ms. Antonellis may have to rely not only her technical expertise but the valuable communication skills she learned at CBS.

“Part of my responsibility is to take technology-based ideas and take it out of the techie space,” she said. “If executives look at me like I have three heads, then I’ve failed as an executive.”