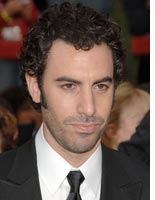

Throw the Money Down the Well

How Sacha Baron Cohen's agents made a slick deal for Bruno.

Posted Wednesday, March 14, 2007, at 12:57 PM ET

Funny business: When Fox let slip the opportunity to make Bruno, Sacha Baron Cohen's follow-up to Borat, some thought the studio let one of the hottest stars in the firmament get away. Others said the deal, which cost more than $40 million, was too rich—especially since it's an open question whether Cohen can pull off another movie based on people not recognizing him (this time as a gay Austrian fashion maven).

The Bruno deal raises another good question: Has Endeavor, the agency that represents Cohen, invented the perfect crime? Or did it simply come up with a clever way of striking a very favorable deal that infuriates the studios?

Endeavor has had some Oscar heat lately—its clients include Martin Scorsese, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and many others (though Reese Witherspoon just bolted). Even before Borat opened, the agency presided over a bidding war for Bruno among several studios. Universal's winning bid was $42.5 million—a big bump up from Borat, which cost less than $20 million (and has grossed more than $250 million worldwide).

Before the bidding frenzy started, Endeavor sold Bruno to a financing entity called Media Rights Capital. MRC didn't take much of a risk, since the studios were fighting to buy the project before the proverbial ink was dry. In fact, MRC sold the package to Universal at such lightning speed that some at the studios have wondered aloud (if not on the record): Why did Endeavor need to bring MRC into the deal?

And that raises the question: Is MRC a separate company, or is it Endeavor in different clothing? It is against California state law for agencies to produce films, and Endeavor has said that MRC is a separate entity. But some in Hollywood perceive MRC as a unit of Endeavor—a unit positioned to cherry-pick projects. Former Endeavor agent Modi Wiczyk is co-CEO of MRC.

One executive who passed on Bruno said MRC seems to be an "internal production machine" for the agency. An executive at another company also expressed doubts about the deal. "None of the math made sense," this executive said. Estimating high, the film seemed to require a budget of only about $30 million, "even if you give Sacha the $15 million that he wanted" for starring. And if that were true, then whose pocket would be lined with the markup?

An Endeavor source says all this is the bitter cavil of the defeated. "MRC is its own company," he says. After all, Endeavor would hardly risk its business by breaking the law. And through the independent MRC, Endeavor got Cohen one hell of a deal (and presumably an extra-nice commission for itself). MRC agreed to pay Cohen $15 million instead of the $12.5 that a studio would have paid, and gave him the lion's share of profits as well as creative control. And in the end, he gets to own the negative—a worrisome prospect for studios that live on the income thrown off by their libraries. That's a package the studios would never have matched—much less beaten—without an electric prod.

One of those executives who did not think the deal was well-advised sees it as a bad precedent, explaining that a studio "should not step into a deal where you're violating the most basic practices of the business you're in."

Executives at Universal disagree. "One could argue if you did this all the time that it's a bad way to run your business," one says. "We're not doing this all the time. But there are unique opportunities."

The eventual deal with Universal was all the sweeter for Cohen because at the time that it was struck, the research tracking audience interest in Borat looked a little wobbly and Fox—figuring that the movie needed to build a little word-of-mouth in the heartland where no one had ever heard of Cohen—cut the number of theaters in which the film would open. None of that sat well with the star. And Fox did not respond to the opportunity to make the Bruno deal with the alacrity that Cohen or his representatives deemed appropriate.

For its $42.5 million, Universal got rights to the movie in English-speaking countries, Germany, Austria, and let us not forget Belgium and the Netherlands (but apparently not Kazakhstan). Our Endeavor source tells us this is a bargain. Cohen's Ali G movie did $15 million in the United Kingdom in the pre-Borat days, he says, and Borat pulled in almost $40 million there. So (he argues), it made sense for Universal to wager that Bruno can pull in enough money even in its limited territories—one of which is the United States, after all. (Bear in mind that studios get to keep about half of those grosses. But the Endeavor source says Universal cannot lose money on the movie even if it's terrible.)

This source says the studios are annoyed simply because they were backed into a corner. "People say, 'We're never going to work with you again—fuck you,' " he says cheerfully. "Two months later, there's something they want. … The studios are getting less powerful, not more. Did we do the right thing for our client? That's a no-brainer."